This service was from a long long time ago, it

seems. Before, frankly, I was very good

at all! But I decided to put really old

stuff here as well, because progress is progress.

We lit the chalice – obviously.

But I didn’t write the words down that we used . . . did I mention it

was a very long time ago?

The story was this:

The sermon went like this:

This morning seems a good morning to be

talking about Freedom (as if there were ever a morning which isn’t), given that

it’s the first day of “smoke free England”.

There is, of course, a view that this new legislation is a curtailment

of smokers’ rights. But there is also a

view – and it’s mine – that’s it’s a declaration of the rights of non-smokers.

In fact, far be it from me to use this as a forum for gloating, but “hurrah”!

And that’s – if you’ll excuse the slightly

stretched and obscure pun – the rub.

Like so many any other issues about freedom, it’s not a universal

liberation. Right or wrong, fair or not,

in the interests of public health or just in the cause of a nanny state, some

people are now unable to do something they could do this time yesterday. Freedom is seldom without a price.

The reading Helaina shared with us is from

Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. If you haven’t read it, read it. I will try not to spoil the plot too much: as

well as being a horrifying, sobering read, it is a brilliantly crafted

read. Written in 1985, The Handmaid’s Tale is set in the

Republic of Gilead, in what is now Massachusetts, in a then-future late

twentieth century.

The name Gilead is, of course, biblical,

and refers – amongst other things to the hymn that says “There is a balm in Gilead that makes the spirit whole. There is a balm in Gilead that heals the

sin-sick soul”. Society in Gilead is

based on a bastardised version of a selection of bible passages, dissent is

punishable by death; women’s rights have been suddenly and catastrophically

removed, and the enforcement of rigid social roles is swift and sickeningly

severe. Women are no longer allowed to

work or to own money. These changes

happen suddenly, with women being sent home from work and their bank accounts

being transferred to their husbands, fathers or partners. Other changes happen slowly – as the

protagonist says “nothing changes

instantaneously: in a gradually heating bathtub you’d be boiled to death before

you knew it”.

Women’s fertility has also become a matter

of state regulation. All fertile women

(for in the book there are precious few of them) become ‘handmaids’ and are

assigned to a high ranking male official, and their one role in life is to bear

him children. If they fail to do so,

they are exiled to the colonies, where, like other infertile women they die a

slow and painful death. There are, of

course, other roles for women: wives,

“marthas”, who are domestic servants, and daughters. There is no movement between roles, and every

item of a woman’s clothing denotes her rank.

Handmaids wear red robes, with wings to prevent eye contact. Every aspect of life is ruled and regulated –

conversations are limited to platitudes, the only entertainment available is

public executions and – more rarely – public birthings.

Nearly as horrifically to most of us, all

form of reading matter is banned. Not

just magazines, or books, or anything-except-the-bible, but all reading matter. Shops no longer have names, just pictures of

what they sell. The protagonist finds a

cushion, embroidered with the word “faith”, and this becomes her greatest treasure,

not because of the illegal luxury of softness, but because of the illegal

luxury of words.

What is perhaps most frightening about

Atwood’s dystopian vision is that none of it is entirely made up. There is nothing in the novel, from public

participation in executions to a warped allegiance to a deliberately biased form

of the bible that cannot be traced to some real civilisation.

But what is also frightening is that Atwood

manages to make some aspects of the regime attractive. Certainly, the first time I read the book, at

about 18, I didn’t find it entirely negative.

The order, the surface calm, the assigned roles, the lack of

responsibility to do anything other than what you are told, all hold a certain

charm.

There is, indeed, a balm in Gilead, for

those who chose to accept blindly, although it would be a stretch to say that

it either makes the wounded whole or heals a sin-sick soul. The film version, a few years later, is

certainly visually stunning, and if you can ignore the underlying brutality, it

is easy to swallow the promise of “freedom from”. And I think we can all sometimes be guilty of

allowing ourselves to ignore the underlying brutality.

Because “freedom from” is a very tempting

proposition. I think at some level we

would all like to be free from responsibility, to be free from having to

decide, to have someone tell us that if we do so-and-so we will be fine and

safe and rewarded. Freedom from can

certainly be easier. I have always been,

on one level, slightly envious of people who can just swallow a dogma whole and

live by it. Although, intellectually, we

know that mind control is a bad thing, that brainwashing is wrong and that

cults – religious or otherwise – are dangerous, there must be something to be

said for having your every decision made for you, your every belief fed to you

and your every question answered for you.

Just think of all the decisions you’ve had

the freedom to make, just this morning, just up to now. When, and indeed whether, to wake up; whether

to get up then, or turn over for five more minutes or an hour or the rest of the

day; what to have for breakfast, or not to have breakfast; tea, or coffee, or

juice – herbal, fruit, earl grey or bog standard – cup or mug, milk or not,

sugar or not; whether to leave the empty cup on the table, or stack it for

later, or wash it up. Whether to put the

TV on, or the radio, or some music, or nothing.

Whether to shower, bath or wash at the sink, whether to wash your hair,

what soap or shampoo or shower gel or perfume to wear. What clothes to put on. Whether to iron them, or wear yesterday’s, or

wear whatever’s clean or worry about the holes in them or whether you wore the

same thing last week. Whether to come to

church or not. Whether to leave on time,

or a bit late. Whether you really need

your coat, or your umbrella. Which route

to use to get here. Whether to listen to

music on your journey, or talk to someone, or think, or let your mind drift, or

make a shopping list in your head. Where

to sit. Who to chat to, or whether to

chat to anyone. Whether to help light

the chalice, whether to light a candle, whether it should be a joy or a

concern. Whether to join in the hymns,

whether to sing the melody or a harmony.

Whether to join in with the prayers and meditations, or to think your

own thoughts or to pray your own prayers.

Whether to listen to the technical mastery of the musical interlude, or

let the feelings wash over you, or chatter, or meditate or think or ignore

it.

And that’s just a couple of hours’ worth of

decisions we were all free to make.

Stretch those decisions out over a day, then a week, then a month and a

year and a lifetime, and our freedom is really quite mind-boggling. It is, as the Ralph Waldo Emerson said “awful

to look into the mind of man and see how free we are” – bearing in mind that

when Emerson was writing, awful meant “full of awe”, not “bad”.

Those are exactly the sorts of freedoms

that the protagonist of The Handmaid’s

Tale gets the most emotional about.

She talks clinically about the lack of financial freedom, and with a

perhaps necessary detachment about her role as a child bearer for another

woman’s husband, but with loss and hurt and love about postcards and the

ability to write on them.

It is not for nothing that the highest form

of state sanction in this country – and to my mind, any country that dares to

call itself civilized – is the removal of freedom. The worst punishment a court can hand down in

the UK, is that of imprisonment. And

whatever the arguments about lengths of sentences, and ease of life in today’s

prisons, and whether prison even works, one thing is clear to me – that

convicted criminals are sent to prison as

a punishment, not to be punished. The lack of freedom is the punishment. Almost

every one of those daily freedoms I’ve listed is removed from almost all

prisoners.

And it’s not only in the legal and penal

system that removal of freedom is that last resort – anyone who is deemed to

need psychiatric treatment against their will is subject to a very thorough

assessment before it can be decided – by a panel of people including medical

staff, psychiatric staff and social workers – that they should have their

liberty removed. It is never something

which is done lightly, although, like convictions and imprisonment, it is too

often done wrongly or unjustly.

Those small daily freedoms we have may seem

trivial. But their very triviality is

what makes them precious. I am aware

that I’ve not mentioned the history of slavery and abolition, or modern day

slavery, or sex trafficking or sweatshops or economic or political

freedom. Those subjects are too huge to

cover here, and need services of their own.

Some are soon to have them.

So, where does our Unitarianism fit in all

this? We are certainly not offered the

freedom from responsibility and freedom from decision-making I mentioned

earlier. We cannot come and sit here,

Sunday after Sunday, in the calm and trusting knowledge that we are being told

what is right and true and eternal. We

can’t come and sit here and be told what to do and what not to do and where to

go and who to trade with and who to associate with and know that if we go along

with that we’ll be okay in this world and more importantly in another one. It would be categorically impossible to

believe in or agree with everything everyone says who stands up here. We would have to be able to hold directly

contradictory opinions at the same time.

If we have a moral or theological or spiritual problem or issue to

discuss, we cannot turn to our book of dogma and find an answer, or turn to an

ordained leader and be given an answer.

Unitarianism offers us freedom from other

things – freedom from the expectation to believe in things we may find hard to

swallow, freedom from the obligation to believe the same thing consistently, freedom

from an expectation that we will trust anyone’s word and experience as being

more valid than our own. And it offers

us freedom to as well: freedom to

think, and to reason, and to come to our own conclusions and form our own

beliefs - and crucially, to express

those conclusions and beliefs; freedom to doubt and to be discouraged and to

get fed up and to disagree; freedom to participate in whatever way we feel

comfortable, freedom to be busy and active or to simply participate by being

here.

But those freedoms are also

responsibilities. If we have freedom of

choice, and freedom of thought and freedom of belief, then I believe we have a

responsibility to use them. I won’t say

to use them wisely, because we can

never know until afterwards whether we’ve chosen wisely or not. We are lucky enough to live in a society with

a relatively well functioning democracy, and in which we are entitled to

vote. It is foolish of us not to, or at

least, if we don’t, to have a good reason not to. It is also, given the sacrifices that have

been made to win the vote – and not just for women – rather rude. By the same token, we are fortunate – or

wise, or brave – enough to have found our spiritual or worshipping home here,

and it would be foolish and irresponsible of us to throw that away by not, at

least, ensuring that we do think our own thoughts and find our own

beliefs.

We are all, I hope, aware of the evils of

slavery and oppression and totalitarianism and imprisonment and restrictions on

religious expression. And we are all, I

hope, aware of the blessing and grace that is our freedom from those

evils. But I am aware that I, for one,

am not always fully conscious and appreciative of the tiny, trivial freedoms

that I enjoy and that others do not. And

I believe that it would do none of us any harm to start looking at those

freedoms and enjoying them consciously.

We sang:

Life that maketh all things new.

We shall be strong and free

Faith of the free

For the healing of the nations

With joy we claim the growing light

Our readings were:

From Trainspotting,

John Hodge:

Choose

Life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a big television,

choose washing machines, cars, compact disc players and electrical tin openers.

Choose good health, low cholesterol, and dental insurance. Choose fixed

interest mortgage repayments. Choose a starter home. Choose your friends.

Choose leisurewear and matching luggage. Choose a three-piece suite on hire

purchase in a range of fabrics. Choose DIY and wondering who you are on a

Sunday morning. Choose sitting on that couch watching mind-numbing,

spirit-crushing game shows, stuffing junk food into your mouth. Choose your

future. Choose life

From A Handmaid’s

Tale, Margaret Atwood

In returning my pass, the guard bends his head to try

to look at my face.

I raise my head a little, to help him, and he sees my

eyes, and I see his, and he blushes. He is the one who turns away.

It’s an event.

A small defiance of rule, so small as to be undetectable, but such

moments are the rewards I hold out for myself, like the candy I hoarded as a

child, at the back of a drawer.

Such moments are possibilities, tiny peepholes.

It’s hotel rooms I miss. The fresh towels, the wastebaskets gaping

their invitations. I was careless, in

those rooms. There were postcards, with

pictures on them, and you could write on the postcards and send them to anyone

you wanted. It seems like such an

impossible thing now, like something you’d make up.

I think about laundromats. What I wore to them: shorts, jeans, jogging

pants. What I put into them: my own

clothes, my own soap, my own money, money I had earned myself.

I think about having such control.

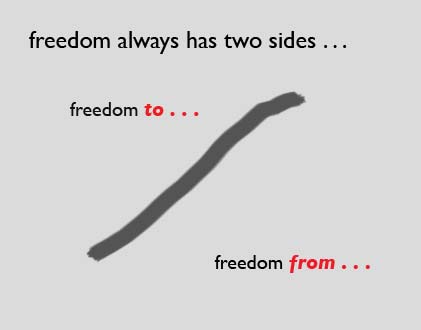

There is more than one kind of freedom, said Aunt

Lydia. Freedom to, and freedom

from.

In the days of anarchy, it was freedom to. Now you are being given freedom from. Don’t underrate it.

And from Ralph Waldo Emerson:

My

life is a May game. I will live as I

like. I defy your strait-laced, weary,

social ways and modes. Blue is the sky,

green the fields and groves, fresh the springs, glad the rivers, and hospitable

the splendour of sun and star. I will

play my game out. And if any shall say

me nay, shall come out with swords and staves against me, come and

welcome. I will not look grave for such

a fool’s matter. I cannot lose my cheer

for such trumpery. Life is a May game

still.

Freedom

is necessary. If you please to plant

yourself on the side of Fate and say, Fate is all, then we say, a part of fate

is the freedom of man. Forever wells up

the impulse of choosing and acting in the soul.

Intellect annuls fate. So far as

a man thinks, he is free.

It

is awful to look into the mind of man and see how free we are, to what

frightful excesses our vices may run under the whited wall of a respectable

reputation. Outside, among your fellows,

among strangers, you must preserve appearance, a hundred things you cannot do;

but inside, the terrible freedom!

There were spoken prayers and a

benediction, but neither of them were orginal and I can’t find them, so they’re

not here!